The lost art of language

Getting my car towed & being glad AI hasn't replaced my elementary school Spanish skills

For my entire life, I’ve longed to fluently speak a second language.

My mother grew up speaking Arabic, but only a few words have found their way into my lexicon; namely terms of endearment like “gulbi”, which means “my heart”, and the occasional “yallah” as a real catch all. While I struggled with elementary Spanish, my sister is a polyglot. She speaks Spanish like a local and is regularly mistaken for one.

Me and Duolingo exist like passing ships in the night. We reconnect every few months when I realize how little Spanish I remember, only for me to flounder on airport or grocery store vocab.

Recently, I had a moment of “thank God I paid attention in Spanish class”.

This August, I found myself in a relatively isolated area of Portugal, waiting 7 hours for a tow truck to get our unable-to-start rental car, with 1% left on the one phone between the two of us traveling together. Luckily, the small surf beach was a camper’s paradise, mostly for Spanish-speaking visitors. I mustered up every bit of confidence I had and went van to van, asking any camper to lend us a phone charger, using my broken Spanish.

I think I probably got out some version of “Tu tienes un cord por mi teléfono? El teléfono tiene nada! Cero! Tienes energía para mi teléfono?”. It was enough to get a lovely Spanish family to hand over a portable charger, which gave us just enough battery to get through the day.

I was thankful for elementary school Spanish, my one quarter of Spanish required to graduate college, and some undeserved confidence. After recovering from the bleak day, I wondered: what will this scenario look like in a few years, when we all have tools that make languages feel like a fraction of the barrier they are today?

The fact that a single human can learn multiple languages is fascinating. Just look to children — “kids really can learn the whole variety of human languages. And that’s for an interesting reason, which is that languages are evolved to be learned by kids. So a language can’t survive as a language if it’s not learnable”, says cognitive scientist Michael Frank. Languages are inherently learnable and structured, making them perfect for large language models to be able to adapt to them.

ChatGPT supports 59 languages. However, model performance still relies heavily on the amount of data available online, meaning that languages left out of the digital ecosystem are harder for ChatGPT to perform tasks on. Given the variance in performance by language, more AI-generated content will appear online in a handful of languages, createing a feedback loop where high-resource languages keep getting richer, while lower-resource ones risk further marginalization.

OpenAI is highly motivated to get its products into the hands of non-English-speaking users for this reason. Both OpenAI and Perplexity recently announced offering their AI tools to users in India for free — a data-acquisition play to improve model performance and user experience in their native languages before eventually introducing paid tiers.

There’s a dream world in which tools like ChatGPT actually enable preservation of languages. Preserving a language will require input from native speakers training models, especially if there is very little training data available online. As a 6th grader, we were required to take Latin, which was deemed a positive for my future SAT scores but useless for conversation. If there had been a way to practice Latin on-demand, powered by AI, I’m sure I’d remember far more today than I do. A tool like Speak would have done wonders for my skills, providing an AI-powered tutor that could converse with me 24/7, for a fraction of the cost of a tutor.

Beyond preservation, AI opens up opportunity for communication across languages in real-time. Tools like Toby or Apple’s native translation stack will provide economic value, like hiring a non-English speaker for an upcoming work project or opening up opportunities for folks who have been previously been limited to offering services in a single language. More of these tools will move to our phones, so it’s clear why Apple is making a play here.

I’d be curious to track the percent of English speakers worldwide over time, with post-ChatGPT as the reference point for potential inflection. I’d bet we will see more English spoken worldwide as a result. We definitely won’t lose languages altogether — geography, culture, evolving dialects, and unevenly distributed access to technology ensure they’ll persist even in an age of AI. What we may lose is the traditional way we learn them. Learning a language in the future will be faster and cheaper, but also easier to avoid as real-time translation becomes common practice.

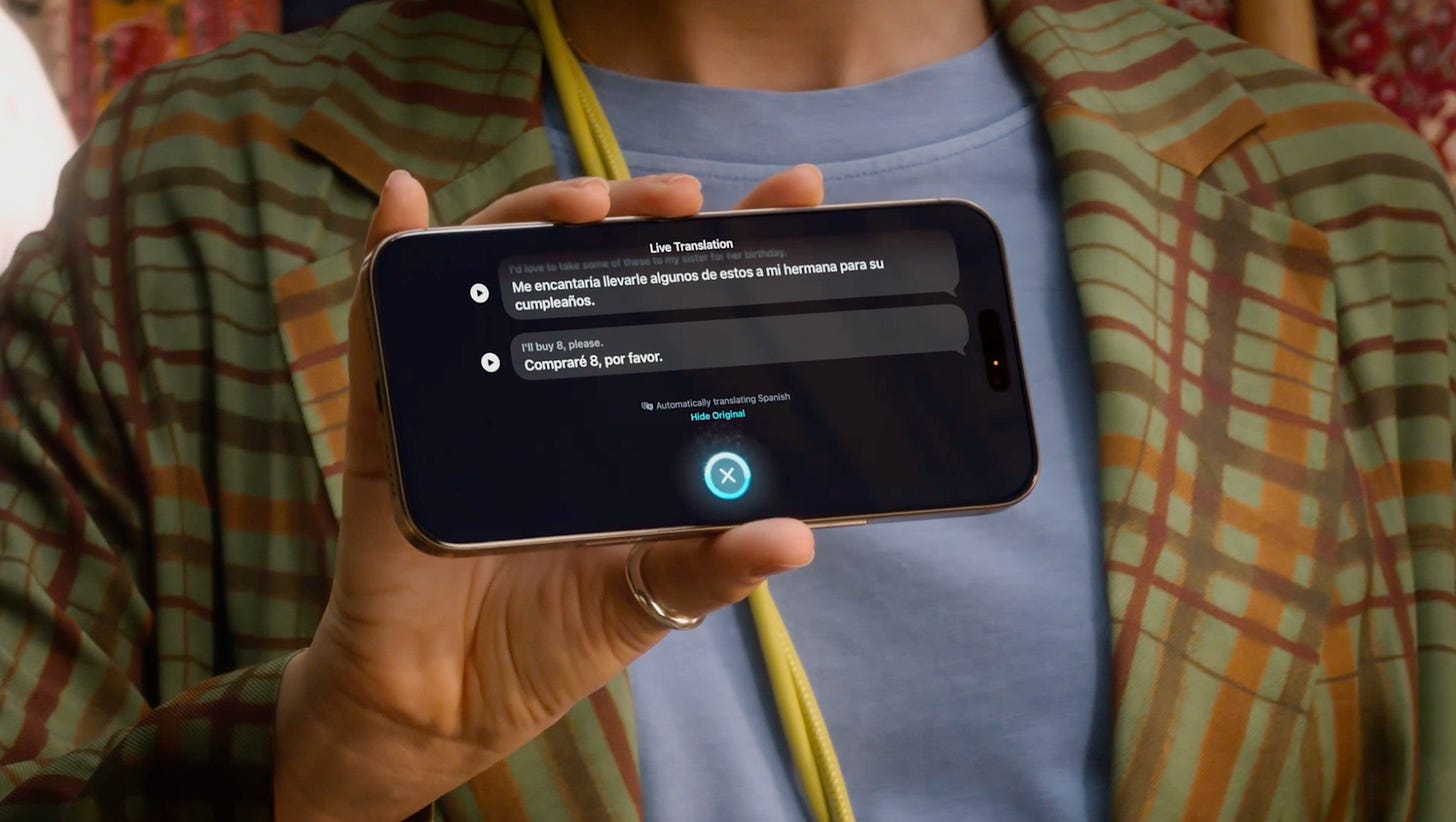

Two weeks after my dire moments in Portugal, Apple launched Live Translation.

In Messages, Live Translation can automatically translate a user’s response as they type and deliver it in the recipient’s language. During FaceTime calls, users can follow along with live translated captions while still hearing their friend or family member’s voice. And during a phone call, the translation is spoken out loud in real time. Users can access Live Translation on AirPods with an all-new gesture by simultaneously pressing both AirPods stems; by saying “Siri, start Live Translation;” or even from the Action button on iPhone, which will allow them to hear in their preferred language.

While the demos feel a bit clunky, the result is that the gap between hardware and software providing value for multi-lingual experiences is closing.

We’re moving rapidly towards a future where an AirPod in your ear can break any barrier that language has been in the past. I could speak in Arabic with my grandfather. I could order a glass of wine in Italian.

But, perhaps an over-reliance on AI wouldn’t have helped me when I was service-less, phone-less and without a car in Portugal. Looking back, I’m forever grateful I paid enough attention in elementary Spanish to get through that day. But perhaps AI would also accelerate my ability to learn a new language, so I would have had far more confidence, landing the right words the first try instead of stumbling through.

I’ve always viewed language learning as an art. We’ve culturally tied being multi-lingual as a desirable goal. Perhaps we’ll lose some of that art over time. However, the opportunity outweighs that art — democratizing language learning, reducing costs, economic opportunity for non-English speakers, and preservation of old languages. A world where the barriers of language start to break down is one that I’m eager to be a part of.

De me mucho gusta, hija hermosa.